|

|

WHAT THE MOON SAW:

AND OTHER TALES.

Waldemar Daa and his Daughters. p. 122.

Waldemar Daa and his Daughters. p. 122.

WHAT THE MOON SAW:

AND OTHER TALES.

BY

HANS C. ANDERSEN.

PREFACE.

The present book is put forth as a sequel to the volume of Hans C.

Andersen's "Stories and Tales," published in a similar form in the

course of 1864. It contains tales and sketches various in character;

and following, as it does, an earlier volume, care has been taken to

intersperse with the children's tales stories which, by their graver

character and deeper meaning, are calculated to interest those

"children of a larger growth" who can find instruction as well as

amusement in the play of fancy and imagination, though the realm be

that of fiction, and the instruction be conveyed in a simple form.

The series of sketches of "What the Moon Saw," with which the present

volume opens, arose from the experiences of Andersen, when as a youth

he went to seek his fortune in the capital of his native land; and the

story entitled "Under the Willow Tree" is said likewise to have its

foundation in fact; indeed, it seems redolent of the truth of that

natural human love and suffering which is so truly said to "make the

whole world kin."

On the preparation and embellishment of the book, the same care and

attention have been lavished as on the preceding volume. The pencil of

Mr. Bayes and the graver of the Brothers Dalziel have again been

employed in the work of illustration; and it is hoped that the favour

bestowed by the public on the former volume may be extended to this

its successor.

H. W. D.

my post of observation.

my post of observation.

WHAT THE MOON SAW.

INTRODUCTION.

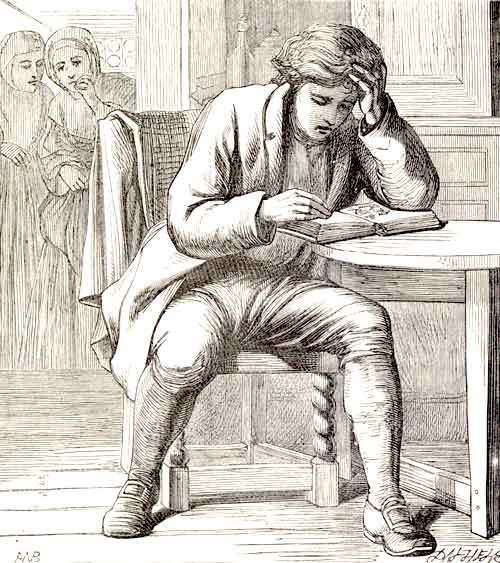

It is a strange thing, that when I feel most fervently and most

deeply, my hands and my tongue seem alike tied, so that I cannot[2]

rightly describe or accurately portray the thoughts that are rising

within me; and yet I am a painter: my eye tells me as much as that,

and all my friends who have seen my sketches and fancies say the same.

I am a poor lad, and live in one of the narrowest of lanes; but I do

not want for light, as my room is high up in the house, with an

extensive prospect over the neighbouring roofs. During the first few

days I went to live in the town, I felt low-spirited and solitary

enough. Instead of the forest and the green hills of former days, I

had here only a forest of chimney-pots to look out upon. And then I

had not a single friend; not one familiar face greeted me.

So one evening I sat at the window, in a desponding mood; and

presently I opened the casement and looked out. Oh, how my heart

leaped up with joy! Here was a well-known face at last—a round,

friendly countenance, the face of a good friend I had known at home.

In, fact it was the Moon that looked in upon me. He was quite

unchanged, the dear old Moon, and had the same face exactly that he

used to show when he peered down upon me through the willow trees on

the moor. I kissed my hand to him over and over again, as he shone far

into my little room; and he, for his part, promised me that every

evening, when he came abroad, he would look in upon me for a few

moments. This promise he has faithfully kept. It is a pity that he can

only stay such a short time when he comes. Whenever he appears, he

tells me of one thing or another that he has seen on the previous

night, or on that same evening. "Just paint the scenes I describe to

you"—this is what he said to me—"and you will have a very pretty

picture-book." I have followed his injunction for many evenings. I

could make up a new "Thousand and One Nights," in my own way, out of

these pictures, but the number might be too great, after all. The

pictures I have here given have not been chosen at random, but follow

in their proper order, just as they were described to me. Some great

gifted painter, or some poet or musician, may make something more of

them if he likes; what I have given here are only hasty sketches,

hurriedly put upon the paper, with some of my own thoughts

interspersed; for the Moon did not come to me every evening—a cloud

sometimes hid his face from me.[3]

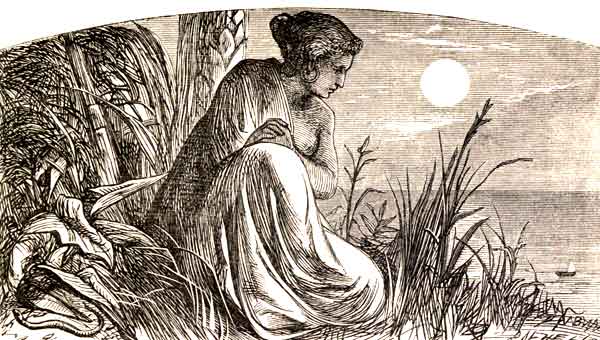

the indian girl.

the indian girl.

First Evening.

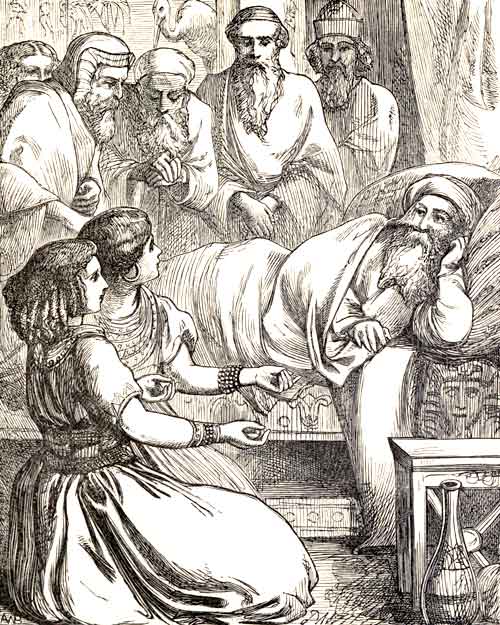

"Last night"—I am quoting the Moon's own words—"last night I was

gliding through the cloudless Indian sky. My face was mirrored in the

waters of the Ganges, and my beams strove to pierce through the thick

intertwining boughs of the bananas, arching beneath me like the

tortoise's shell. Forth from the thicket tripped a Hindoo maid, light

as a gazelle, beautiful as Eve. Airy and ethereal as a vision, and yet

sharply defined amid the surrounding shadows, stood this daughter of

Hindostan: I could read on her delicate brow the thought that had

brought her hither. The thorny creeping plants tore her sandals, but

for all that she came rapidly forward. The deer that had come down to

the river to quench their thirst, sprang by with a startled bound, for

in her hand the maiden bore a lighted lamp. I could see the blood in

her delicate finger tips, as she spread them for a screen before the

dancing flame. She came down to the stream, and set the lamp upon the

water, and let it float away. The flame flickered to and fro, and

seemed ready to expire; but still the lamp burned on, and the girl's

black sparkling eyes, half veiled behind their long silken lashes,

followed it with a gaze of earnest intensity. She knew that if the

lamp continued to burn so long as she could keep it in sight, her

betrothed was still alive; but if the lamp was suddenly extinguished,

he[4] was dead. And the lamp burned bravely on, and she fell on her

knees, and prayed. Near her in the grass lay a speckled snake, but she

heeded it not—she thought only of Bramah and of her betrothed. 'He

lives!' she shouted joyfully, 'he lives!' And from the mountains the

echo came back upon her, 'he lives!'"

the little girl and the chickens.

the little girl and the chickens.

Second Evening.

"Yesterday," said the Moon to me, "I looked down upon a small

courtyard surrounded on all sides by houses. In the courtyard sat a

clucking hen with eleven chickens; and a pretty little girl was

running and jumping around them. The hen was frightened, and screamed,

and spread out her wings over the little brood. Then the girl's father

came[5] out and scolded her; and I glided away and thought no more of

the matter.

"But this evening, only a few minutes ago, I looked down into the same

courtyard. Everything was quiet. But presently the little girl came

forth again, crept quietly to the hen-house, pushed back the bolt, and

slipped into the apartment of the hen and chickens. They cried out

loudly, and came fluttering down from their perches, and ran about in

dismay, and the little girl ran after them. I saw it quite plainly,

for I looked through a hole in the hen-house wall. I was angry with

the wilful child, and felt glad when her father came out and scolded

her more violently than yesterday, holding her roughly by the arm: she

held down her head, and her blue eyes were full of large tears. 'What

are you about here?' he asked. She wept and said, 'I wanted to kiss

the hen and beg her pardon for frightening her yesterday; but I was

afraid to tell you.'

"And the father kissed the innocent child's forehead, and I kissed her

on the mouth and eyes."

Third Evening.

"In the narrow street round the corner yonder—it is so narrow that my

beams can only glide for a minute along the walls of the house, but in

that minute I see enough to learn what the world is made of—in that

narrow street I saw a woman. Sixteen years ago that woman was a child,

playing in the garden of the old parsonage, in the country. The hedges

of rose-bush were old, and the flowers were faded. They straggled wild

over the paths, and the ragged branches grew up among the boughs of

the apple trees; here and there were a few roses still in bloom—not

so fair as the queen of flowers generally appears, but still they had

colour and scent too. The clergyman's little daughter appeared to me a

far lovelier rose, as she sat on her stool under the straggling hedge,

hugging and caressing her doll with the battered pasteboard cheeks.

"Ten years afterwards I saw her again. I beheld her in a splendid

ball-room: she was the beautiful bride of a rich merchant. I rejoiced

at her happiness, and sought her on calm quiet evenings—ah, nobody

thinks of my clear eye and my silent glance! Alas! my rose ran wild,

like the rose bushes in the garden of the parsonage. There are

tragedies in every-day life, and to-night I saw the last act of one.

"She was lying in bed in a house in that narrow street: she was sick[6]

unto death, and the cruel landlord came up, and tore away the thin

coverlet, her only protection against the cold. 'Get up!' said he;

'your face is enough to frighten one. Get up and dress yourself, give

me money, or I'll turn you out into the street! Quick—get up!' She

answered, 'Alas! death is gnawing at my heart. Let me rest.' But he

forced her to get up and bathe her face, and put a wreath of roses in

her hair; and he placed her in a chair at the window, with a candle

burning beside her, and went away.

"I looked at her, and she was sitting motionless, with her hands in

her lap. The wind caught the open window and shut it with a crash, so

that a pane came clattering down in fragments; but still she never

moved. The curtain caught fire, and the flames played about her face;

and I saw that she was dead. There at the open window sat the dead

woman, preaching a sermon against sin—my poor faded rose out of the

parsonage garden!"

Fourth Evening.

"This evening I saw a German play acted," said the Moon. "It was in a

little town. A stable had been turned into a theatre; that is to say,

the stable had been left standing, and had been turned into private

boxes, and all the timber work had been covered with coloured paper. A

little iron chandelier hung beneath the ceiling, and that it might be

made to disappear into the ceiling, as it does in great theatres, when

the ting-ting of the prompter's bell is heard, a great inverted tub

had been placed just above it.

the play in a stable.

the play in a stable.

"'Ting-ting!' and the little iron chandelier suddenly rose at least

half a yard and disappeared in the tub; and that was the sign that the

play was going to begin. A young nobleman and his lady, who happened

to be passing through the little town, were present at the

performance, and consequently the house was crowded. But under the

chandelier was a vacant space like a little crater: not a single soul

sat there, for the tallow was dropping, drip, drip! I saw everything,

for it was so warm in there that every loophole had been opened. The

male and female servants stood outside, peeping through the chinks,

although a real policeman was inside, threatening them with a stick.

Close by the orchestra could be seen the noble young couple in two old

arm-chairs, which were usually occupied by his worship the mayor and

his lady; but these latter were to-day obliged to content themselves

with wooden forms, just as if they had been ordinary citizens; and the

lady observed[7] quietly to herself, 'One sees, now, that there is rank

above rank;' and this incident gave an air of extra festivity to the

whole proceedings. The chandelier gave little leaps, the crowd got

their knuckles rapped, and I, the Moon, was present at the performance

from beginning to end."

[8]

Fifth Evening.

"Yesterday," began the Moon, "I looked down upon the turmoil of Paris.

My eye penetrated into an apartment of the Louvre. An old grandmother,

poorly clad—she belonged to the working class—was following one of

the under-servants into the great empty throne-room, for this was the

apartment she wanted to see—that she was resolved to see; it had cost

her many a little sacrifice, and many a coaxing word, to penetrate

thus far. She folded her thin hands, and looked round with an air of

reverence, as if she had been in a church.

"'Here it was!' she said, 'here!' And she approached the throne, from

which hung the rich velvet fringed with gold lace. 'There,' she

exclaimed, 'there!' and she knelt and kissed the purple carpet. I

think she was actually weeping.

"'But it was not this very velvet!' observed the footman, and a

smile played about his mouth. 'True, but it was this very place,'

replied the woman, 'and it must have looked just like this.' 'It

looked so, and yet it did not,' observed the man: 'the windows were

beaten in, and the doors were off their hinges, and there was blood

upon the floor.' 'But for all that you can say, my grandson died upon

the throne of France. Died!' mournfully repeated the old woman. I do

not think another word was spoken, and they soon quitted the hall. The

evening twilight faded, and my light shone doubly vivid upon the rich

velvet that covered the throne of France.

"Now, who do you think this poor woman was? Listen, I will tell you a

story.

"It happened, in the Revolution of July, on the evening of the most

brilliantly victorious day, when every house was a fortress, every

window a breastwork. The people stormed the Tuileries. Even women and

children were to be found among the combatants. They penetrated into

the apartments and halls of the palace. A poor half-grown boy in a

ragged blouse fought among the older insurgents. Mortally wounded with

several bayonet thrusts, he sank down. This happened in the

throne-room. They laid the bleeding youth upon the throne of France,

wrapped the velvet around his wounds, and his blood streamed forth

upon the imperial purple. There was a picture! the splendid hall, the

fighting groups! A torn flag lay upon the ground, the tricolor was

waving above the bayonets, and on the throne lay the poor lad with the

pale glorified countenance, his eyes turned towards the sky, his limbs

writhing in the death agony, his breast bare, and his poor tattered[9]

clothing half hidden by the rich velvet embroidered with silver

lilies. At the boy's cradle a prophecy had been spoken: 'He will die

on the throne of France!' The mother's heart dreamt of a second

Napoleon.

"My beams have kissed the wreath of immortelles on his grave, and

this night they kissed the forehead of the old grandame, while in a

dream the picture floated before her which thou mayest draw—the poor

boy on the throne of France."

Sixth Evening.

"I've been in Upsala," said the Moon: "I looked down upon the great

plain covered with coarse grass, and upon the barren fields. I

mirrored my face in the Tyris river, while the steamboat drove the

fish into the rushes. Beneath me floated the waves, throwing long

shadows on the so-called graves of Odin, Thor, and Friga. In the

scanty turf that covers the hill-side names have been cut.[1] There is

no monument here, no memorial on which the traveller can have his name

carved, no rocky wall on whose surface he can get it painted; so

visitors have the turf cut away for that purpose. The naked earth

peers through in the form of great letters and names; these form a

network over the whole hill. Here is an immortality, which lasts till

the fresh turf grows!

"Up on the hill stood a man, a poet. He emptied the mead horn with the

broad silver rim, and murmured a name. He begged the winds not to

betray him, but I heard the name. I knew it. A count's coronet

sparkles above it, and therefore he did not speak it out. I smiled,

for I knew that a poet's crown adorns his own name. The nobility of

Eleanora d'Este is attached to the name of Tasso. And I also know

where the Rose of Beauty blooms!"

Thus spake the Moon, and a cloud came between us. May no cloud

separate the poet from the rose!

Seventh Evening.

"Along the margin of the shore stretches a forest of firs and beeches,

and fresh and fragrant is this wood; hundreds of nightingales visit it

[10]every spring. Close beside it is the sea, the ever-changing sea, and

between the two is placed the broad high-road. One carriage after

another rolls over it; but I did not follow them, for my eye loves

best to rest upon one point. A Hun's Grave[2] lies there, and the sloe

and blackthorn grow luxuriantly among the stones. Here is true poetry

in nature.

"And how do you think men appreciate this poetry? I will tell you what

I heard there last evening and during the night.

"First, two rich landed proprietors came driving by. 'Those are

glorious trees!' said the first. 'Certainly; there are ten loads of

firewood in each,' observed the other: 'it will be a hard winter, and

last year we got fourteen dollars a load'—and they were gone. 'The

road here is wretched,' observed another man who drove past. 'That's

the fault of those horrible trees,' replied his neighbour; 'there is

no free current of air; the wind can only come from the sea'—and they

were gone. The stage coach went rattling past. All the passengers were

asleep at this beautiful spot. The postillion blew his horn, but he

only thought, 'I can play capitally. It sounds well here. I wonder if

those in there like it?'—and the stage coach vanished. Then two young

fellows came gallopping up on horseback. There's youth and spirit in

the blood here! thought I; and, indeed, they looked with a smile at

the moss-grown hill and thick forest. 'I should not dislike a walk

here with the miller's Christine,' said one—and they flew past.

"The flowers scented the air; every breath of air was hushed: it

seemed as if the sea were a part of the sky that stretched above the

deep valley. A carriage rolled by. Six people were sitting in it. Four

of them were asleep; the fifth was thinking of his new summer coat,

which would suit him admirably; the sixth turned to the coachman and

asked him if there were anything remarkable connected with yonder heap

of stones. 'No,' replied the coachman, 'it's only a heap of stones;

but the trees are remarkable.' 'How so?' 'Why, I'll tell you how they

are very remarkable. You see, in winter, when the snow lies very deep,

and has hidden the whole road so that nothing is to be seen, those

trees serve me for a landmark. I steer by them, so as not to drive

into the sea; and you see that is why the trees are remarkable.'

the poor girl rests on the hun's grave.

the poor girl rests on the hun's grave.

"Now came a painter. He spoke not a word, but his eyes sparkled. He

began to whistle. At this the nightingales sang louder than ever.

'Hold your tongues!' he cried testily; and he made accurate notes of

[11]all the colours and transitions—blue, and lilac, and dark brown.

'That will make a beautiful picture,' he said. He took it in just as a

mirror takes in a view; and as he worked he whistled a march of

Rossini. And last of all came a poor girl. She laid aside the burden

she carried, and sat down to rest upon the Hun's Grave. Her pale

handsome face was bent in a listening attitude towards the forest. Her

eyes brightened, she gazed earnestly at the sea and the sky, her hands

were folded, and I think she prayed, 'Our Father.' She herself could

not understand the feeling that swept through her, but I know that

this minute, and the beautiful natural scene, will live within her

memory for years, far more vividly and more truly than the painter

could portray it with his colours on paper. My rays followed her till

the morning dawn kissed her brow."

[12]

Eighth Evening.

Heavy clouds obscured the sky, and the Moon did not make his

appearance at all. I stood in my little room, more lonely than ever,

and looked up at the sky where he ought to have shown himself. My

thoughts flew far away, up to my great friend, who every evening told

me such pretty tales, and showed me pictures. Yes, he has had an

experience indeed. He glided over the waters of the Deluge, and smiled

on Noah's ark just as he lately glanced down upon me, and brought

comfort and promise of a new world that was to spring forth from the

old. When the Children of Israel sat weeping by the waters of Babylon,

he glanced mournfully upon the willows where hung the silent harps.

When Romeo climbed the balcony, and the promise of true love fluttered

like a cherub toward heaven, the round Moon hung, half hidden among

the dark cypresses, in the lucid air. He saw the captive giant at St.

Helena, looking from the lonely rock across the wide ocean, while

great thoughts swept through his soul. Ah! what tales the Moon can

tell. Human life is like a story to him. To-night I shall not see thee

again, old friend. To-night I can draw no picture of the memories of

thy visit. And, as I looked dreamily towards the clouds, the sky

became bright. There was a glancing light, and a beam from the Moon

fell upon me. It vanished again, and dark clouds flew past; but still

it was a greeting, a friendly good-night offered to me by the Moon.

Ninth Evening.

The air was clear again. Several evenings had passed, and the Moon was

in the first quarter. Again he gave me an outline for a sketch. Listen

to what he told me.

"I have followed the polar bird and the swimming whale to the eastern

coast of Greenland. Gaunt ice-covered rocks and dark clouds hung over

a valley, where dwarf willows and barberry bushes stood clothed in

green. The blooming lychnis exhaled sweet odours. My light was faint,

my face pale as the water lily that, torn from its stem, has been

drifting for weeks with the tide. The crown-shaped Northern Light

burned fiercely in the sky. Its ring was broad, and from its

circumference the rays shot like whirling shafts of fire across the

whole sky, flashing in changing radiance from green to red. The

inhabitants of that icy region were assembling for dance and

festivity; but, accustomed[13] to this glorious spectacle, they scarcely

deigned to glance at it. 'Let us leave the souls of the dead to their

ball-play with the heads of the walruses,' they thought in their

superstition, and they turned their whole attention to the song and

dance. In the midst of the circle, and divested of his furry cloak,

stood a Greenlander, with a small pipe, and he played and sang a song

about catching the seal, and the chorus around chimed in with, 'Eia,

Eia, Ah.' And in their white furs they danced about in the circle,

till you might fancy it was a polar bear's ball.

"And now a Court of Judgment was opened. Those Greenlanders who had

quarrelled stepped forward, and the offended person chanted forth the

faults of his adversary in an extempore song, turning them sharply

into ridicule, to the sound of the pipe and the measure of the dance.

The defendant replied with satire as keen, while the audience laughed,

and gave their verdict. The rocks heaved, the glaciers melted, and

great masses of ice and snow came crashing down, shivering to

fragments as they fell: it was a glorious Greenland summer night. A

hundred paces away, under the open tent of hides, lay a sick man. Life

still flowed through his warm blood, but still he was to die—he

himself felt it, and all who stood round him knew it also; therefore

his wife was already sowing round him the shroud of furs, that she

might not afterwards be obliged to touch the dead body. And she asked,

'Wilt thou be buried on the rock, in the firm snow? I will deck the

spot with thy kayak, and thy arrows, and the angekokk shall dance

over it. Or wouldst thou rather be buried in the sea?' 'In the sea,'

he whispered, and nodded with a mournful smile. 'Yes, it is a pleasant

summer tent, the sea,' observed the wife. 'Thousands of seals sport

there, the walrus shall lie at thy feet, and the hunt will be safe and

merry!' And the yelling children tore the outspread hide from the

window-hole, that the dead man might be carried to the ocean, the

billowy ocean, that had given him food in life, and that now, in

death, was to afford him a place of rest. For his monument, he had the

floating, ever-changing icebergs, whereon the seal sleeps, while the

storm bird flies round their gleaming summits!"

Tenth Evening.

the old maid.

the old maid.

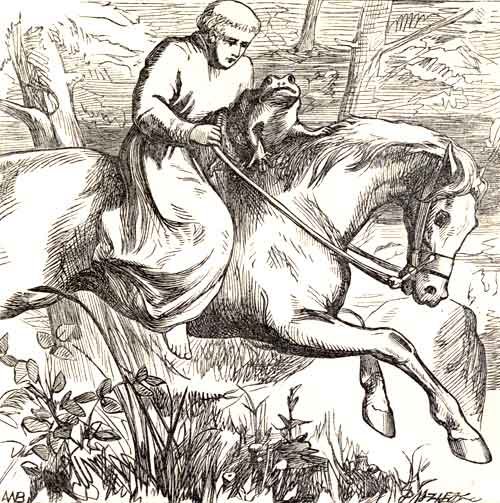

"I knew an old maid," said the Moon. "Every winter she wore a wrapper

of yellow satin, and it always remained new, and was the only fashion

she followed. In summer she always wore the same straw hat, and I

verily believe the very same grey-blue dress.[14]

"She never went out, except across the street to an old female friend;

and in later years she did not even take this walk, for the old friend

was dead. In her solitude my old maid was always busy at the window,

which was adorned in summer with pretty flowers, and in winter with

cress, grown upon felt. During the last months I saw her no more at

the window, but she was still alive. I knew that, for I had not yet

seen her begin the 'long journey,' of which she often spoke with her

friend. 'Yes, yes,' she was in the habit of saying, 'when I come to

die,[15] I shall take a longer journey than I have made my whole life

long. Our family vault is six miles from here. I shall be carried

there, and shall sleep there among my family and relatives.' Last

night a van stopped at the house. A coffin was carried out, and then I

knew that she was dead. They placed straw round the coffin, and the

van drove away. There slept the quiet old lady, who had not gone out

of her house once for the last year. The van rolled out through the

town-gate as briskly as if it were going for a pleasant excursion. On

the high-road the pace was quicker yet. The coachman looked nervously

round every now and then—I fancy he half expected to see her sitting

on the coffin, in her yellow satin wrapper. And because he was

startled, he foolishly lashed his horses, while he held the reins so

tightly that the poor beasts were in a foam: they were young and

fiery. A hare jumped across the road and startled them, and they

fairly ran away. The old sober maiden, who had for years and years

moved quietly round and round in a dull circle, was now, in death,

rattled over stock and stone on the public highway. The coffin in its

covering of straw tumbled out of the van, and was left on the

high-road, while horses, coachman, and carriage flew past in wild

career. The lark rose up carolling from the field, twittering her

morning lay over the coffin, and presently perched upon it, picking

with her beak at the straw covering, as though she would tear it up.

The lark rose up again, singing gaily, and I withdrew behind the red

morning clouds."

Eleventh Evening.

"I will give you a picture of Pompeii," said the Moon. "I was in the

suburb in the Street of Tombs, as they call it, where the fair

monuments stand, in the spot where, ages ago, the merry youths, their

temples bound with rosy wreaths, danced with the fair sisters of Laïs.

Now, the stillness of death reigned around. German mercenaries, in the

Neapolitan service, kept guard, played cards, and diced; and a troop

of strangers from beyond the mountains came into the town, accompanied

by a sentry. They wanted to see the city that had risen from the grave

illumined by my beams; and I showed them the wheel-ruts in the streets

paved with broad lava slabs; I showed them the names on the doors, and

the signs that hung there yet: they saw in the little courtyard the

basins of the fountains, ornamented with shells; but no jet of water

gushed upwards, no songs sounded forth from the richly-painted

chambers, where the bronze dog kept the door.[16]

"It was the City of the Dead; only Vesuvius thundered forth his

everlasting hymn, each separate verse of which is called by men an

eruption. We went to the temple of Venus, built of snow-white marble,

with its high altar in front of the broad steps, and the weeping

willows sprouting freshly forth among the pillars. The air was

transparent and blue, and black Vesuvius formed the background, with

fire ever shooting forth from it, like the stem of the pine tree.

Above it stretched the smoky cloud in the silence of the night, like

the crown of the pine, but in a blood-red illumination. Among the

company was a lady singer, a real and great singer. I have witnessed

the homage paid to her in the greatest cities of Europe. When they

came to the tragic theatre, they all sat down on the amphitheatre

steps, and thus a small part of the house was occupied by an audience,

as it had been many centuries ago. The stage still stood unchanged,

with its walled side-scenes, and the two arches in the background,

through which the beholders saw the same scene that had been exhibited

in the old times—a scene painted by nature herself, namely, the

mountains between Sorento and Amalfi. The singer gaily mounted the

ancient stage, and sang. The place inspired her, and she reminded me

of a wild Arab horse, that rushes headlong on with snorting nostrils

and flying mane—her song was so light and yet so firm. Anon I thought

of the mourning mother beneath the cross at Golgotha, so deep was the

expression of pain. And, just as it had done thousands of years ago,

the sound of applause and delight now filled the theatre. 'Happy,

gifted creature!' all the hearers exclaimed. Five minutes more, and

the stage was empty, the company had vanished, and not a sound more

was heard—all were gone. But the ruins stood unchanged, as they will

stand when centuries shall have gone by, and when none shall know of

the momentary applause and of the triumph of the fair songstress; when

all will be forgotten and gone, and even for me this hour will be but

a dream of the past."

Twelfth Evening.

"I looked through the windows of an editor's house," said the Moon.

"It was somewhere in Germany. I saw handsome furniture, many books,

and a chaos of newspapers. Several young men were present: the editor

himself stood at his desk, and two little books, both by young

authors, were to be noticed. 'This one has been sent to me,' said he.

'I have not read it yet; what think you of the contents?' 'Oh,' said

the person addressed—he was a poet himself—'it is good enough;[17] a

little broad, certainly; but, you see, the author is still young. The

verses might be better, to be sure; the thoughts are sound, though

there is certainly a good deal of commonplace among them. But what

will you have? You can't be always getting something new. That he'll

turn out anything great I don't believe, but you may safely praise

him. He is well read, a remarkable Oriental scholar, and has a good

judgment. It was he who wrote that nice review of my 'Reflections on

Domestic Life.' We must be lenient towards the young man.'

"'But he is a complete hack!' objected another of the gentlemen.

'Nothing is worse in poetry than mediocrity, and he certainly does not

go beyond this.'

"'Poor fellow,' observed a third, 'and his aunt is so happy about him.

It was she, Mr. Editor, who got together so many subscribers for your

last translation.'

"'Ah, the good woman! Well, I have noticed the book briefly. Undoubted

talent—a welcome offering—a flower in the garden of poetry—prettily

brought out—and so on. But this other book—I suppose the author

expects me to purchase it? I hear it is praised. He has genius,

certainly; don't you think so?'

"'Yes, all the world declares as much,' replied the poet, 'but it has

turned out rather wildly. The punctuation of the book, in particular,

is very eccentric.'

"'It will be good for him if we pull him to pieces, and anger him a

little, otherwise he will get too good an opinion of himself.'

"'But that would be unfair,' objected the fourth. 'Let us not carp at

little faults, but rejoice over the real and abundant good that we

find here: he surpasses all the rest.'

"'Not so. If he is a true genius, he can bear the sharp voice of

censure. There are people enough to praise him. Don't let us quite

turn his head.'

"'Decided talent,' wrote the editor, 'with the usual carelessness.

That he can write incorrect verses may be seen in page 25, where there

are two false quantities. We recommend him to study the ancients,

etc.'

"I went away," continued the Moon, "and looked through the windows in

the aunt's house. There sat the be-praised poet, the tame one; all

the guests paid homage to him, and he was happy.

"I sought the other poet out, the wild one; him also I found in a

great assembly at his patron's, where the tame poet's book was being

discussed.

"'I shall read yours also,' said Mæcenas; 'but to speak honestly—you[18]

know I never hide my opinion from you—I don't expect much from it,

for you are much too wild, too fantastic. But it must be allowed that,

as a man, you are highly respectable.'

"A young girl sat in a corner; and she read in a book these words:

"'In the dust lies genius and glory,

But ev'ry-day talent will pay.

It's only the old, old story,

But the piece is repeated each day.'"

Thirteenth Evening.

The Moon said, "Beside the woodland path there are two small

farmhouses. The doors are low, and some of the windows are placed

quite high, and others close to the ground; and whitethorn and

barberry bushes grow around them. The roof of each house is overgrown

with moss and with yellow flowers and houseleek. Cabbage and potatoes

are the only plants cultivated in the gardens, but out of the hedge

there grows a willow tree, and under this willow tree sat a little

girl, and she sat with her eyes fixed upon the old oak tree between

the two huts.

"It was an old withered stem. It had been sawn off at the top, and a

stork had built his nest upon it; and he stood in this nest clapping

with his beak. A little boy came and stood by the girl's side: they

were brother and sister.

"'What are you looking at?' he asked.

"'I'm watching the stork,' she replied: 'our neighbours told me that

he would bring us a little brother or sister to-day; let us watch to

see it come!'

"'The stork brings no such things,' the boy declared, 'you may be sure

of that. Our neighbour told me the same thing, but she laughed when

she said it, and so I asked her if she could say 'On my honour,' and

she could not; and I know by that that the story about the storks is

not true, and that they only tell it to us children for fun.'

"'But where do the babies come from, then?' asked the girl.

"'Why, an angel from heaven brings them under his cloak, but no man

can see him; and that's why we never know when he brings them.'

"At that moment there was a rustling in the branches of the willow

tree, and the children folded their hands and looked at one another:

it was certainly the angel coming with the baby. They took each

other's hand, and at that moment the door of one of the houses opened,

and the neighbour appeared.[19]

watching the stork.

watching the stork.

"'Come in, you two,' she said. 'See what the stork has brought. It is

a little brother.'

"And the children nodded gravely at one another, for they had felt

quite sure already that the baby was come."

Fourteenth Evening.

"I was gliding over the Lüneburg Heath," the Moon said. "A lonely hut

stood by the wayside, a few scanty bushes grew near it, and a[20]

nightingale who had lost his way sang sweetly. He died in the coldness

of the night: it was his farewell song that I heard.

"The morning dawn came glimmering red. I saw a caravan of emigrant

peasant families who were bound to Hamburgh, there to take ship for

America, where fancied prosperity would bloom for them. The mothers

carried their little children at their backs, the elder ones tottered

by their sides, and a poor starved horse tugged at a cart that bore

their scanty effects. The cold wind whistled, and therefore the little

girl nestled closer to the mother, who, looking up at my decreasing

disc, thought of the bitter want at home, and spoke of the heavy taxes

they had not been able to raise. The whole caravan thought of the same

thing; therefore, the rising dawn seemed to them a message from the

sun, of fortune that was to gleam brightly upon them. They heard the

dying nightingale sing: it was no false prophet, but a harbinger of

fortune. The wind whistled, therefore they did not understand that the

nightingale sung, 'Fare away over the sea! Thou hast paid the long

passage with all that was thine, and poor and helpless shalt thou

enter Canaan. Thou must sell thyself, thy wife, and thy children. But

your griefs shall not last long. Behind the broad fragrant leaves

lurks the goddess of Death, and her welcome kiss shall breathe fever

into thy blood. Fare away, fare away, over the heaving billows.' And

the caravan listened well pleased to the song of the nightingale,

which seemed to promise good fortune. Day broke through the light

clouds; country people went across the heath to church: the

black-gowned women with their white head-dresses looked like ghosts

that had stepped forth from the church pictures. All around lay a wide

dead plain, covered with faded brown heath, and black charred spaces

between the white sand hills. The women carried hymn books, and walked

into the church. Oh, pray, pray for those who are wandering to find

graves beyond the foaming billows."

Fifteenth Evening.

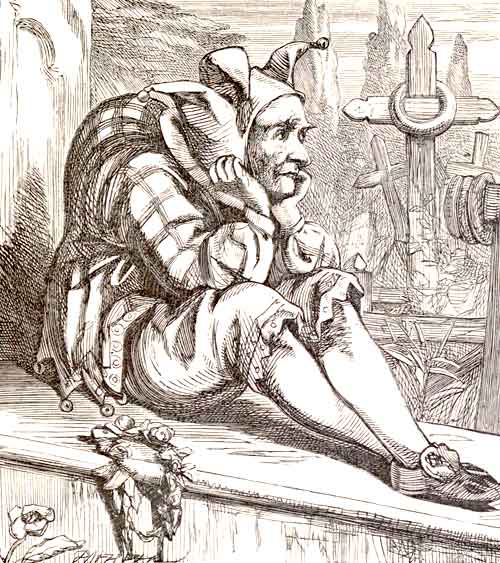

pulcinella on columbine's grave.

pulcinella on columbine's grave.

"I know a Pulcinella,"[3] the Moon told me. "The public applaud

vociferously directly they see him. Every one of his movements is

comic, and is sure to throw the house into convulsions of laughter;

and yet there is no art in it all—it is complete nature. When he was

yet [21]a little boy, playing about with other boys, he was already

Punch. Nature had intended him for it, and had provided him with a

hump on his back, and another on his breast; but his inward man, his

mind, on the contrary, was richly furnished. No one could surpass him

in depth[22] of feeling or in readiness of intellect. The theatre was his

ideal world. If he had possessed a slender well-shaped figure, he

might have been the first tragedian on any stage: the heroic, the

great, filled his soul; and yet he had to become a Pulcinella. His

very sorrow and melancholy did but increase the comic dryness of his

sharply-cut features, and increased the laughter of the audience, who

showered plaudits on their favourite. The lovely Columbine was indeed

kind and cordial to him; but she preferred to marry the Harlequin. It

would have been too ridiculous if beauty and ugliness had in reality

paired together.

"When Pulcinella was in very bad spirits, she was the only one who

could force a hearty burst of laughter, or even a smile from him:

first she would be melancholy with him, then quieter, and at last

quite cheerful and happy. 'I know very well what is the matter with

you,' she said; 'yes, you're in love!' And he could not help laughing.

'I and Love!' he cried, 'that would have an absurd look. How the

public would shout!' 'Certainly, you are in love,' she continued; and

added with a comic pathos, 'and I am the person you are in love with.'

You see, such a thing may be said when it is quite out of the

question—and, indeed, Pulcinella burst out laughing, and gave a leap

into the air, and his melancholy was forgotten.

"And yet she had only spoken the truth. He did love her, love her

adoringly, as he loved what was great and lofty in art. At her wedding

he was the merriest among the guests, but in the stillness of night he

wept: if the public had seen his distorted face then, they would have

applauded rapturously.

"And a few days ago, Columbine died. On the day of the funeral,

Harlequin was not required to show himself on the boards, for he was a

disconsolate widower. The director had to give a very merry piece,

that the public might not too painfully miss the pretty Columbine and

the agile Harlequin. Therefore Pulcinella had to be more boisterous

and extravagant than ever; and he danced and capered, with despair in

his heart; and the audience yelled, and shouted 'bravo, bravissimo!'

Pulcinella was actually called before the curtain. He was pronounced

inimitable.

"But last night the hideous little fellow went out of the town, quite

alone, to the deserted churchyard. The wreath of flowers on

Columbine's grave was already faded, and he sat down there. It was a

study for a painter. As he sat with his chin on his hands, his eyes

turned up towards me, he looked like a grotesque monument—a Punch on

a grave—peculiar and whimsical! If the people could have seen their

favourite, they would have cried as usual, 'Bravo, Pulcinella; bravo,

bravissimo!'"[23]

Sixteenth Evening.

Hear what the Moon told me. "I have seen the cadet who had just been

made an officer put on his handsome uniform for the first time; I have

seen the young bride in her wedding dress, and the princess girl-wife

happy in her gorgeous robes; but never have I seen a felicity equal to

that of a little girl of four years old, whom I watched this evening.

She had received a new blue dress, and a new pink hat, the splendid

attire had just been put on, and all were calling for a candle, for my

rays, shining in through the windows of the room, were not bright

enough for the occasion, and further illumination was required. There

stood the little maid, stiff and upright as a doll, her arms stretched

painfully straight out away from the dress, and her fingers apart; and

oh, what happiness beamed from her eyes, and from her whole

countenance! 'To-morrow you shall go out in your new clothes,' said

her mother; and the little one looked up at her hat, and down at her

frock, and smiled brightly. 'Mother,' she cried, 'what will the little

dogs think, when they see me in these splendid new things?'"

Seventeenth Evening.

"I have spoken to you of Pompeii," said the Moon; "that corpse of a

city, exposed in the view of living towns: I know another sight still

more strange, and this is not the corpse, but the spectre of a city.

Whenever the jetty fountains splash into the marble basins, they seem

to me to be telling the story of the floating city. Yes, the spouting

water may tell of her, the waves of the sea may sing of her fame! On

the surface of the ocean a mist often rests, and that is her widow's

veil. The bridegroom of the sea is dead, his palace and his city are

his mausoleum! Dost thou know this city? She has never heard the

rolling of wheels or the hoof-tread of horses in her streets, through

which the fish swim, while the black gondola glides spectrally over

the green water. I will show you the place," continued the Moon, "the

largest square in it, and you will fancy yourself transported into the

city of a fairy tale. The grass grows rank among the broad flagstones,

and in the morning twilight thousands of tame pigeons flutter around

the solitary lofty tower. On three sides you find yourself surrounded

by cloistered walks. In these the silent Turk sits smoking his long

pipe, the handsome Greek leans against the pillar and gazes at the

upraised[24] trophies and lofty masts, memorials of power that is gone.

The flags hang down like mourning scarves. A girl rests there: she has

put down her heavy pails filled with water, the yoke with which she

has carried them rests on one of her shoulders, and she leans against

the mast of victory. That is not a fairy palace you see before you

yonder, but a church: the gilded domes and shining orbs flash back my

beams; the glorious bronze horses up yonder have made journeys, like

the bronze horse in the fairy tale: they have come hither, and gone

hence, and have returned again. Do you notice the variegated splendour

of the walls and windows? It looks as if Genius had followed the

caprices of a child, in the adornment of these singular temples. Do

you see the winged lion on the pillar? The gold glitters still, but

his wings are tied—the lion is dead, for the king of the sea is dead;

the great halls stand desolate, and where gorgeous paintings hung of

yore, the naked wall now peers through. The lazzarone sleeps under

the arcade, whose pavement in old times was to be trodden only by the

feet of high nobility. From the deep wells, and perhaps from the

prisons by the Bridge of Sighs, rise the accents of woe, as at the

time when the tambourine was heard in the gay gondolas, and the golden

ring was cast from the Bucentaur to Adria, the queen of the seas.

Adria! shroud thyself in mists; let the veil of thy widowhood shroud

thy form, and clothe in the weeds of woe the mausoleum of thy

bridegroom—the marble, spectral Venice."

Eighteenth Evening.

"I looked down upon a great theatre," said the Moon. "The house was

crowded, for a new actor was to make his first appearance that night.

My rays glided over a little window in the wall, and I saw a painted

face with the forehead pressed against the panes. It was the hero of

the evening. The knightly beard curled crisply about the chin; but

there were tears in the man's eyes, for he had been hissed off, and

indeed with reason. The poor Incapable! But Incapables cannot be

admitted into the empire of Art. He had deep feeling, and loved his

art enthusiastically, but the art loved not him. The prompter's bell

sounded; 'the hero enters with a determined air,' so ran the stage

direction in his part, and he had to appear before an audience who

turned him into ridicule. When the piece was over, I saw a form

wrapped in a mantle, creeping down the steps: it was the vanquished

knight of the evening. The scene-shifters whispered to one another,

and I followed the poor fellow home to his room. To hang one's self is

to die a mean[25] death, and poison is not always at hand, I know; but he

thought of both. I saw how he looked at his pale face in the glass,

with eyes half closed, to see if he should look well as a corpse. A

man may be very unhappy, and yet exceedingly affected. He thought of

death, of suicide; I believe he pitied himself, for he wept bitterly,

and when a man has had his cry out he doesn't kill himself.

"Since that time a year had rolled by. Again a play was to be acted,

but in a little theatre, and by a poor strolling company. Again I saw

the well-remembered face, with the painted cheeks and the crisp beard.

He looked up at me and smiled; and yet he had been hissed off only a

minute before—hissed off from a wretched theatre, by a miserable

audience. And to-night a shabby hearse rolled out of the town-gate. It

was a suicide—our painted, despised hero. The driver of the hearse

was the only person present, for no one followed except my beams. In a

corner of the churchyard the corpse of the suicide was shovelled into

the earth, and nettles will soon be growing rankly over his grave, and

the sexton will throw thorns and weeds from the other graves upon it."

Nineteenth Evening.

"I come from Rome," said the Moon. "In the midst of the city, upon one

of the seven hills, lie the ruins of the imperial palace. The wild fig

tree grows in the clefts of the wall, and covers the nakedness thereof

with its broad grey-green leaves; trampling among heaps of rubbish,

the ass treads upon green laurels, and rejoices over the rank

thistles. From this spot, whence the eagles of Rome once flew abroad,

whence they 'came, saw, and conquered,' our door leads into a little

mean house, built of clay between two pillars; the wild vine hangs

like a mourning garland over the crooked window. An old woman and her

little granddaughter live there: they rule now in the palace of the

Cæsars, and show to strangers the remains of its past glories. Of the

splendid throne-hall only a naked wall yet stands, and a black cypress

throws its dark shadow on the spot where the throne once stood. The

dust lies several feet deep on the broken pavement; and the little

maiden, now the daughter of the imperial palace, often sits there on

her stool when the evening bells ring. The keyhole of the door close

by she calls her turret window; through this she can see half Rome, as

far as the mighty cupola of St. Peter's.

"On this evening, as usual, stillness reigned around; and in the[26] full

beam of my light came the little granddaughter. On her head she

carried an earthen pitcher of antique shape filled with water. Her

feet were bare, her short frock and her white sleeves were torn. I

kissed her pretty round shoulders, her dark eyes, and black shining

hair. She mounted the stairs; they were steep, having been made up of

rough blocks of broken marble and the capital of a fallen pillar. The

coloured lizards slipped away, startled, from before her feet, but she

was not frightened at them. Already she lifted her hand to pull the

door-bell—a hare's foot fastened to a string formed the bell-handle

of the imperial palace. She paused for a moment—of what might she be

thinking? Perhaps of the beautiful Christ-child, dressed in gold and

silver, which was down below in the chapel, where the silver

candlesticks gleamed so bright, and where her little friends sung the

hymns in which she also could join? I know not. Presently she moved

again—she stumbled; the earthen vessel fell from her head, and broke

on the marble steps. She burst into tears. The beautiful daughter of

the imperial palace wept over the worthless broken pitcher; with her

bare feet she stood there weeping, and dared not pull the string, the

bell-rope of the imperial palace!"

Twentieth Evening.

It was more than a fortnight since the Moon had shone. Now he stood

once more, round and bright, above the clouds, moving slowly onward.

Hear what the Moon told me.

"From a town in Fezzan I followed a caravan. On the margin of the

sandy desert, in a salt plain, that shone like a frozen lake, and was

only covered in spots with light drifting sand, a halt was made. The

eldest of the company—the water gourd hung at his girdle, and on his

head was a little bag of unleavened bread—drew a square in the sand

with his staff, and wrote in it a few words out of the Koran, and then

the whole caravan passed over the consecrated spot. A young merchant,

a child of the East, as I could tell by his eye and his figure, rode

pensively forward on his white snorting steed. Was he thinking,

perchance, of his fair young wife? It was only two days ago that the

camel, adorned with furs and with costly shawls, had carried her, the

beauteous bride, round the walls of the city, while drums and cymbals

had sounded, the women sang, and festive shots, of which the

bridegroom fired the greatest number, resounded round the camel; and

now he was journeying with the caravan across the desert.[27]

"For many nights I followed the train. I saw them rest by the

well-side among the stunted palms; they thrust the knife into the

breast of the camel that had fallen, and roasted its flesh by the

fire. My beams cooled the glowing sands, and showed them the black

rocks, dead islands in the immense ocean of sand. No hostile tribes

met them in their pathless route, no storms arose, no columns of sand

whirled destruction over the journeying caravan. At home the beautiful

wife prayed for her husband and her father. 'Are they dead?' she asked

of my golden crescent; 'Are they dead?' she cried to my full disc. Now

the desert lies behind them. This evening they sit beneath the lofty

palm trees, where the crane flutters round them with its long wings,

and the pelican watches them from the branches of the mimosa. The

luxuriant herbage is trampled down, crushed by the feet of elephants.

A troop of negroes are returning from a market in the interior of the

land: the women, with copper buttons in their black hair, and decked

out in clothes dyed with indigo, drive the heavily-laden oxen, on

whose backs slumber the naked black children. A negro leads a young

lion which he has bought, by a string. They approach the caravan; the

young merchant sits pensive and motionless, thinking of his beautiful

wife, dreaming, in the land of the blacks, of his white fragrant lily

beyond the desert. He raises his head, and——" But at this moment a

cloud passed before the Moon, and then another. I heard nothing more

from him this evening.

Twenty-first Evening.

"I saw a little girl weeping," said the Moon; "she was weeping over

the depravity of the world. She had received a most beautiful doll as

a present. Oh, that was a glorious doll, so fair and delicate! She did

not seem created for the sorrows of this world. But the brothers of

the little girl, those great naughty boys, had set the doll high up in

the branches of a tree, and had run away.

the little girl's trouble.

the little girl's trouble.

"The little girl could not reach up to the doll, and could not help

her down, and that is why she was crying. The doll must certainly have

been crying too; for she stretched out her arms among the green

branches, and looked quite mournful. Yes, these are the troubles of

life of which the little girl had often heard tell. Alas, poor doll!

it began to grow dark already; and suppose night were to come on

completely! Was she to be left sitting there alone on the bough all

night long? No, the little maid could not make up her mind to that.

'I'll stay with you,' she said, although she felt anything but happy

in her mind. She could[28] almost fancy she distinctly saw little gnomes,

with their high-crowned hats, sitting in the bushes; and further back

in the long walk, tall spectres appeared to be dancing. They came

nearer and nearer, and stretched out their hands towards the tree on

which the doll sat; they laughed scornfully, and pointed at her with

their fingers. Oh, how frightened the little maid was! 'But if one has

not done anything wrong,' she thought, 'nothing evil can harm one. I

wonder if I have[29] done anything wrong?' And she considered. 'Oh, yes!

I laughed at the poor duck with the red rag on her leg; she limped

along so funnily, I could not help laughing; but it's a sin to laugh

at animals.' And she looked up at the doll. 'Did you laugh at the duck

too?' she asked; and it seemed as if the doll shook her head."

Twenty-second Evening.

"I looked down upon Tyrol," said the Moon, "and my beams caused the

dark pines to throw long shadows upon the rocks. I looked at the

pictures of St. Christopher carrying the Infant Jesus that are painted

there upon the walls of the houses, colossal figures reaching from the

ground to the roof. St. Florian was represented pouring water on the

burning house, and the Lord hung bleeding on the great cross by the

wayside. To the present generation these are old pictures, but I saw

when they were put up, and marked how one followed the other. On the

brow of the mountain yonder is perched, like a swallow's nest, a

lonely convent of nuns. Two of the sisters stood up in the tower

tolling the bell; they were both young, and therefore their glances

flew over the mountain out into the world. A travelling coach passed

by below, the postillion wound his horn, and the poor nuns looked

after the carriage for a moment with a mournful glance, and a tear

gleamed in the eyes of the younger one. And the horn sounded faint and

more faintly, and the convent bell drowned its expiring echoes."

Twenty-third Evening.

Hear what the Moon told me. "Some years ago, here in Copenhagen, I

looked through the window of a mean little room. The father and mother

slept, but the little son was not asleep. I saw the flowered cotton

curtains of the bed move, and the child peep forth. At first I thought

he was looking at the great clock, which was gaily painted in red and

green. At the top sat a cuckoo, below hung the heavy leaden weights,

and the pendulum with the polished disc of metal went to and fro, and

said 'tick, tick.' But no, he was not looking at the clock, but at his

mother's spinning wheel, that stood just underneath it. That was the

boy's favourite piece of furniture, but he dared not touch it, for if

he meddled with it he got a rap on the knuckles. For hours together,

when his mother was spinning, he would sit quietly by her side,

watching[30] the murmuring spindle and the revolving wheel, and as he sat

he thought of many things. Oh, if he might only turn the wheel

himself! Father and mother were asleep; he looked at them, and looked

at the spinning wheel, and presently a little naked foot peered out of

the bed, and then a second foot, and then two little white legs. There

he stood. He looked round once more, to see if father and mother were

still asleep—yes, they slept; and now he crept softly, softly, in

his short little nightgown, to the spinning wheel, and began to spin.

The thread flew from the wheel, and the wheel whirled faster and

faster. I kissed his fair hair and his blue eyes, it was such a pretty

picture.

"At that moment the mother awoke. The curtain shook, she looked forth,

and fancied she saw a gnome or some other kind of little spectre. 'In

Heaven's name!' she cried, and aroused her husband in a frightened

way. He opened his eyes, rubbed them with his hands, and looked at the

brisk little lad. 'Why, that is Bertel,' said he. And my eye quitted

the poor room, for I have so much to see. At the same moment I looked

at the halls of the Vatican, where the marble gods are enthroned. I

shone upon the group of the Laocoon; the stone seemed to sigh. I

pressed a silent kiss on the lips of the Muses, and they seemed to

stir and move. But my rays lingered longest about the Nile group with

the colossal god. Leaning against the Sphinx, he lies there thoughtful

and meditative, as if he were thinking on the rolling centuries; and

little love-gods sport with him and with the crocodiles. In the horn

of plenty sat with folded arms a little tiny love-god, contemplating

the great solemn river-god, a true picture of the boy at the spinning

wheel—the features were exactly the same. Charming and life-like

stood the little marble form, and yet the wheel of the year has turned

more than a thousand times since the time when it sprang forth from

the stone. Just as often as the boy in the little room turned the

spinning wheel had the great wheel murmured, before the age could

again call forth marble gods equal to those he afterwards formed.

little bertel's ambition.

little bertel's ambition.

"Years have passed since all this happened," the Moon went on to say.

"Yesterday I looked upon a bay on the eastern coast of Denmark.

Glorious woods are there, and high trees, an old knightly castle with

red walls, swans floating in the ponds, and in the background appears,

among orchards, a little town with a church. Many boats, the crews all

furnished with torches, glided over the silent expanse—but these

fires had not been kindled for catching fish, for everything had a

festive look. Music sounded, a song was sung, and in one of the boats

the man stood erect to whom homage was paid by the rest, a tall sturdy

man, wrapped in a cloak. He had blue eyes and long white hair. I knew

him, and[31] thought of the Vatican, and of the group of the Nile, and

the old marble gods. I thought of the simple little room where little

Bertel sat in his night-shirt by the spinning wheel. The wheel of time

has turned, and new gods have come forth from the stone. From the

boats there arose a shout: 'Hurrah, hurrah for Bertel Thorwaldsen!'"

[32]

Twenty-fourth Evening.

"I will now give you a picture from Frankfort," said the Moon. "I

especially noticed one building there. It was not the house in which

Goëthe was born, nor the old Council House, through whose grated

windows peered the horns of the oxen that were roasted and given to

the people when the emperors were crowned. No, it was a private house,

plain in appearance, and painted green. It stood near the old Jews'

Street. It was Rothschild's house.

"I looked through the open door. The staircase was brilliantly

lighted: servants carrying wax candles in massive silver candlesticks

stood there, and bowed low before an old woman, who was being brought

downstairs in a litter. The proprietor of the house stood bare-headed,

and respectfully imprinted a kiss on the hand of the old woman. She

was his mother. She nodded in a friendly manner to him and to the

servants, and they carried her into the dark narrow street, into a

little house, that was her dwelling. Here her children had been born,

from hence the fortune of the family had arisen. If she deserted the

despised street and the little house, fortune would also desert her

children. That was her firm belief."

The Moon told me no more; his visit this evening was far too short.

But I thought of the old woman in the narrow despised street. It would

have cost her but a word, and a brilliant house would have arisen for

her on the banks of the Thames—a word, and a villa would have been

prepared in the Bay of Naples.

"If I deserted the lowly house, where the fortunes of my sons first

began to bloom, fortune would desert them!" It was a superstition, but

a superstition of such a class, that he who knows the story and has

seen this picture, need have only two words placed under the picture

to make him understand it; and these two words are: "A mother."

Twenty-fifth Evening.

"It was yesterday, in the morning twilight"—these are the words the

Moon told me—"in the great city no chimney was yet smoking—and it

was just at the chimneys that I was looking. Suddenly a little head

emerged from one of them, and then half a body, the arms resting on

the rim of the chimney-pot. 'Ya-hip! ya-hip!' cried a voice. It was

the little chimney-sweeper, who had for the first time in his life

crept[33] through a chimney, and stuck out his head at the top. 'Ya-hip!

ya-hip!' Yes, certainly that was a very different thing to creeping

about in the dark narrow chimneys! the air blew so fresh, and he could

look over the whole city towards the green wood. The sun was just

rising. It shone round and great, just in his face, that beamed with

triumph, though it was very prettily blacked with soot.

"'The whole town can see me now,' he exclaimed, 'and the moon can see

me now, and the sun too. Ya-hip! ya-hip!' And he flourished his broom

in triumph."

pretty pu.

pretty pu.

Twenty-sixth Evening.

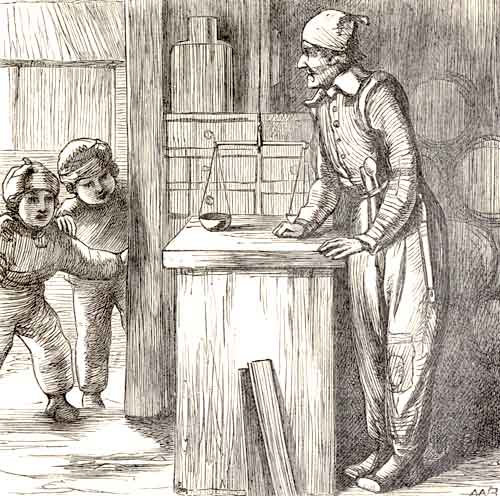

"Last night I looked down upon a town in China," said the Moon. "My

beams irradiated the naked walls that form the streets there. Now and

then, certainly, a door is seen; but it is locked, for what does the

Chinaman care about the outer world? Close wooden shutters covered the

windows behind the walls of the houses; but through the windows[34] of

the temple a faint light glimmered. I looked in, and saw the quaint

decorations within. From the floor to the ceiling pictures are

painted, in the most glaring colours, and richly gilt—pictures

representing the deeds of the gods here on earth. In each niche

statues are placed, but they are almost entirely hidden by the

coloured drapery and the banners that hang down. Before each idol (and

they are all made of tin) stood a little altar of holy water, with

flowers and burning wax lights on it. Above all the rest stood Fo, the

chief deity, clad in a garment of yellow silk, for yellow is here the

sacred colour. At the foot of the altar sat a living being, a young

priest. He appeared to be praying, but in the midst of his prayer he

seemed to fall into deep thought, and this must have been wrong, for

his cheeks glowed and he held down his head. Poor Soui-hong! Was he,

perhaps, dreaming of working in the little flower garden behind the

high street wall? And did that occupation seem more agreeable to him

than watching the wax lights in the temple? Or did he wish to sit at

the rich feast, wiping his mouth with silver paper between each

course? Or was his sin so great that, if he dared utter it, the

Celestial Empire would punish it with death? Had his thoughts ventured

to fly with the ships of the barbarians, to their homes in far distant

England? No, his thoughts did not fly so far, and yet they were

sinful, sinful as thoughts born of young hearts, sinful here in the

temple, in the presence of Fo and the other holy gods.

"I know whither his thoughts had strayed. At the farther end of the

city, on the flat roof paved with porcelain, on which stood the

handsome vases covered with painted flowers, sat the beauteous Pu, of

the little roguish eyes, of the full lips, and of the tiny feet. The

tight shoe pained her, but her heart pained her still more. She lifted

her graceful round arm, and her satin dress rustled. Before her stood

a glass bowl containing four gold-fish. She stirred the bowl carefully

with a slender lacquered stick, very slowly, for she, too, was lost in

thought. Was she thinking, perchance, how the fishes were richly

clothed in gold, how they lived calmly and peacefully in their crystal

world, how they were regularly fed, and yet how much happier they

might be if they were free? Yes, that she could well understand, the

beautiful Pu. Her thoughts wandered away from her home, wandered to

the temple, but not for the sake of holy things. Poor Pu! Poor

Soui-hong!

"Their earthly thoughts met, but my cold beam lay between the two,

like the sword of the cherub."[35]

Twenty-seventh Evening.

"The air was calm," said the Moon; "the water was transparent as the

purest ether through which I was gliding, and deep below the surface I

could see the strange plants that stretched up their long arms towards

me like the gigantic trees of the forest. The fishes swam to and fro

above their tops. High in the air a flight of wild swans were winging

their way, one of which sank lower and lower, with wearied pinions,

his eyes following the airy caravan, that melted farther and farther

into the distance. With outspread wings he sank slowly, as a soap

bubble sinks in the still air, till he touched the water. At length

his head lay back between his wings, and silently he lay there, like a

white lotus flower upon the quiet lake. And a gentle wind arose, and

crisped the quiet surface, which gleamed like the clouds that poured

along in great broad waves; and the swan raised his head, and the

glowing water splashed like blue fire over his breast and back. The

morning dawn illuminated the red clouds, the swan rose strengthened,

and flew towards the rising sun, towards the bluish coast whither the

caravan had gone; but he flew alone, with a longing in his breast.

Lonely he flew over the blue swelling billows."

Twenty-eighth Evening.

"I will give you another picture of Sweden," said the Moon. "Among

dark pine woods, near the melancholy banks of the Stoxen, lies the old

convent church of Wreta. My rays glided through the grating into the

roomy vaults, where kings sleep tranquilly in great stone coffins. On

the wall, above the grave of each, is placed the emblem of earthly

grandeur, a kingly crown; but it is made only of wood, painted and

gilt, and is hung on a wooden peg driven into the wall. The worms have

gnawed the gilded wood, the spider has spun her web from the crown

down to the sand, like a mourning banner, frail and transient as the

grief of mortals. How quietly they sleep! I can remember them quite

plainly. I still see the bold smile on their lips, that so strongly

and plainly expressed joy or grief. When the steamboat winds along

like a magic snail over the lakes, a stranger often comes to the

church, and visits the burial vault; he asks the names of the kings,

and they have a dead and forgotten sound. He glances with a smile at

the worm-eaten crowns, and if he happens to be a pious, thoughtful[36]

man, something of melancholy mingles with the smile. Slumber on, ye

dead ones! The Moon thinks of you, the Moon at night sends down his

rays into your silent kingdom, over which hangs the crown of pine

wood."

Twenty-ninth Evening.

"Close by the high-road," said the Moon, "is an inn, and opposite to

it is a great waggon-shed, whose straw roof was just being

re-thatched. I looked down between the bare rafters and through the

open loft into the comfortless space below. The turkey-cock slept on

the beam, and the saddle rested in the empty crib. In the middle of

the shed stood a travelling carriage; the proprietor was inside, fast

asleep, while the horses were being watered. The coachman stretched

himself, though I am very sure that he had been most comfortably

asleep half the last stage. The door of the servants' room stood open,

and the bed looked as if it had been turned over and over; the candle

stood on the floor, and had burnt deep down into the socket. The wind

blew cold through the shed: it was nearer to the dawn than to

midnight. In the wooden frame on the ground slept a wandering family

of musicians. The father and mother seemed to be dreaming of the

burning liquor that remained in the bottle. The little pale daughter

was dreaming too, for her eyes were wet with tears. The harp stood at

their heads, and the dog lay stretched at their feet."

Thirtieth Evening.

the bear playing at soldiers with the children.

the bear playing at soldiers with the children.

"It was in a little provincial town," the Moon said; "it certainly happened

last year, but that has nothing to do with the matter. I saw it quite

plainly. To-day I read about it in the papers, but there it was not half so

clearly expressed. In the taproom of the little inn sat the bear leader,

eating his supper; the bear was tied up outside, behind the wood pile—poor

Bruin, who did nobody any harm, though he looked grim enough. Up in the

garret three little children were playing by the light of my beams; the

eldest was perhaps six years old, the youngest certainly not more than two.

'Tramp, tramp'—somebody was coming upstairs: who might it be? The door was

thrust open—it was Bruin, the great, shaggy Bruin! He had got tired of

waiting down in the courtyard, and had found his way to the stairs. I saw

it all," said the Moon. "The children were very much frightened at first at

the great[37] shaggy animal; each of them crept into a corner, but he found

them all out, and smelt at them, but did them no harm. 'This must be a

great[38] dog,' they said, and began to stroke him. He lay down upon the

ground, the youngest boy clambered on his back, and bending down a little

head of golden curls, played at hiding in the beast's shaggy skin.

Presently the eldest boy took his drum, and beat upon it till it rattled

again; the bear rose upon his hind legs, and began to dance. It was a

charming sight to behold. Each boy now took his gun, and the bear was

obliged to have one too, and he held it up quite properly. Here was a

capital playmate they had found; and they began marching—one, two; one,

two.

"Suddenly some one came to the door, which opened, and the mother of

the children appeared. You should have seen her in her dumb terror,

with her face as white as chalk, her mouth half open, and her eyes

fixed in a horrified stare. But the youngest boy nodded to her in

great glee, and called out in his infantile prattle, 'We're playing at

soldiers.' And then the bear leader came running up."

Thirty-first Evening.

The wind blew stormy and cold, the clouds flew hurriedly past; only

for a moment now and then did the Moon become visible. He said, "I

looked down from the silent sky upon the driving clouds, and saw the

great shadows chasing each other across the earth. I looked upon a

prison. A closed carriage stood before it; a prisoner was to be

carried away. My rays pierced through the grated window towards the

wall: the prisoner was scratching a few lines upon it, as a parting

token; but he did not write words, but a melody, the outpouring of his

heart. The door was opened, and he was led forth, and fixed his eyes

upon my round disc. Clouds passed between us, as if he were not to see

my face, nor I his. He stepped into the carriage, the door was closed,

the whip cracked, and the horses galloped off into the thick forest,

whither my rays were not able to follow him; but as I glanced through

the grated window, my rays glided over the notes, his last farewell

engraved on the prison wall—where words fail, sounds can often speak.

My rays could only light up isolated notes, so the greater part of

what was written there will ever remain dark to me. Was it the

death-hymn he wrote there? Were these the glad notes of joy? Did he

drive away to meet death, or hasten to the embraces of his beloved?

The rays of the Moon do not read all that is written by mortals."[39]

Thirty-second Evening.

"I love the children," said the Moon, "especially the quite little

ones—they are so droll. Sometimes I peep into the room, between the

curtain and the window frame, when they are not thinking of me. It

gives me pleasure to see them dressing and undressing. First, the

little round naked shoulder comes creeping out of the frock, then the

arm; or I see how the stocking is drawn off, and a plump little white

leg makes its appearance, and a white little foot that is fit to be

kissed, and I kiss it too.

"But about what I was going to tell you. This evening I looked through

a window, before which no curtain was drawn, for nobody lives

opposite. I saw a whole troop of little ones, all of one family, and

among them was a little sister. She is only four years old, but can

say her prayers as well as any of the rest. The mother sits by her bed

every evening, and hears her say her prayers; and then she has a kiss,

and the mother sits by the bed till the little one has gone to sleep,

which generally happens as soon as ever she can close her eyes.

"This evening the two elder children were a little boisterous. One of

them hopped about on one leg in his long white nightgown, and the

other stood on a chair surrounded by the clothes of all the children,